Older People's Experience of Autonomy with Durable Products

Annika Maya-Rivero

Juan Carlos

Ortiz-Nicolás

Centro de Investigaciones de Diseño

Industrial de la Facultad de Arquitectura de le Universidad Nacional Autónoma

de México. Académica RIES.LAC.

Abstract

This article discusses the

importance of promoting autonomy in the design of products for older individuals.

The aim was to better understand the autonomy

experience of older people with durable products. This research utilizes a

qualitative approach to study the experience in-depth and employed six instruments, including

interviews, questionnaires, and a UX curve method, interaction qualities, the psychological needs it

fulfills, and the emotions elicited through the product to investigate

why and how a product, owned by the participant, promotes autonomy. Fourteen Mexican women over the age

of 60, without cognitive impairment,

Spanish-speaking and not affiliated with the design discipline, took part in

the study. The results provide a detailed description of the characteristics of products that

promote autonomy, the interaction properties involved, and the elements that structure the

autonomy experience. The study identified an alignment between intrinsic

motivations and the activity carried out with the product, ease of interaction, and excellent

product performance as components of the experience. The experience of autonomy

is pleasant and enhances well-being.

Keywords: autonomy;

experience; design; older people; design for aging; human-product interaction;

human-centered design.

Introduction

Research in the design for

aging and longevity has increased in recent years. One potential reason

for this is the growth in

healthy life expectancy which has expanded by

8% from 58.3 years in 2000 to 63.7 years in 2019 (World Health

Organization, 2019). Various

issues have been studied in design research, including the importance of

well-being during aging (Reynolds, 2018; Diener & Chan, 2011; Ortiz &

Schoormans, 2022), and ergonomic aspects such as mobility and inclusion through

functional spaces or products (Rivero, 2018).

When discussing design for

the older population, concepts like independence, agency, and autonomy emerge

as significant topics that should be considered to achieve healthy aging goals

and promote a better quality of life. In the case of autonomy, previous

research has linked it to perceived self-efficacy associated with psychological

well-being (Rubio Rubio et al., 2018).

Understanding the constructs of autonomy can help promote autonomous aging through product design and contribute to the advancement of older people's well-being and fulfillment of their human rights (López-García et al., 2022; UN, 2017). Four reasons demonstrate the importance of studying autonomy in older people: a) Autonomy is fundamental to maintain as it naturally decreases with human aging. Additionally, the loss of it is a common fear when entering a geriatric center (Buedo-Guirado & Rubio Rubio, 2018); b) Studying autonomy in older individuals can help ensure that they can exercise their human rights effectively; c) Autonomy has been linked to experiencing satisfying life events (Sheldon et al., 2001) and is closely tied to the ability to act according to one's own will (Deci & Ryan, 1987); d) The evaluation of autonomy perception among community-dwelling older people has been studied in Mexico. The research found that limitations in daily living activities among older individuals were associated with a decreased perception of autonomy (Sánchez-García et al., 2019, p. 2046).

There are several

perspectives on autonomy: 1) It

is recognized as a

human right: The Inter-American Convention on Protecting the Human Rights of

Older People (2017) recognises autonomy as a human right. Article 7 explicitly addresses the right

to independence and autonomy: “Respect for the autonomy of older people in

making their decisions, and for their independence in the actions they

undertake.” Furthermore, the right to autonomy

is reaffirmed in Articles 1[1]

and 22[2].

Therefore, studying autonomy as a strategy to

uphold this right is crucial. 2)Autonomy is a relational construct,

which considers aspects of the individual that contribute to decision-making

(Liu et al., 2022, p. 3) Autonomy as physical aspect of individuals, associated

with daily instrumental activities of life, often measured using scales such as

the Lawton-Brody scale, as health is correlated with longevity and autonomy (Bernardini, 2023). This scale focuses on the functional

aspects of a person, overlooking the personal experience that individuals have

with their autonomy, as previously noted by Lawton & Brody (1969, p. 184)

who stated that “older people's autonomy evaluation and the decision-making

process occurs in the context of the feelings and wishes of the individuals (as

well as their) family members.” 4)Autonomy as a psychological need, which is

defined as the feeling that you are the cause of your actions without the

intervention of external forces or pressures (Sheldon et al.,

2001).

Autonomy User Experience and Design

Moilanen and colleagues (2021) studied older people's perceived

autonomy in residential care. They identified, described, and synthesized

previous research on this topic. The researchers used the constant comparison

method to analyze 46 published studies. They concluded that autonomy is

fundamental in healthcare, particularly in residential care settings. “Autonomy

in this context refers to older people making decisions about their daily

activities while also considering their dignity and human rights” (Moilanen et al., 2021, p. 430). The authors noticed “a

strong connection between the residential care environment and the autonomy of

older individuals” (2021, p. 427). For instance, “older individuals experienced

greater autonomy when care homes involved them in their care plans, allowed

them to decorate their rooms, and listened to their feedback on menus” (2021,

p. 427).

Service

design research, which relied on a variety of methods, such as interviews,

observations, diaries, and a focus group session, identified three primary

qualities of perceived autonomy in older people “1) the ability to make one's

own decisions, 2) completing tasks independently, and 3) having the means to

achieve one's goals” (Miso et al., 2022, p. 8).

In

the field of user experience, previous research has shown that autonomy impacts

people's well-being (Lenz et al., 2013; Tierney & Beattie, 2020; Ortiz

Nicolás & Schoormans, 2019). This is supported by

studies linking autonomy with physical and social well-being (Tierney &

Beattie, 2020) and with satisfactory life events (Sheldon et al., 2001). Desmet and Fokkinga argue that

“autonomy is a fundamental need in human-product interaction, linked to

sub-needs such as freedom of decision, individuality, creative expression, and

self-reliance” (2020, p. 9). It has also been noted that products that people acknowledge as

mediums to promote autonomy

align with their wants,

respond to their commands, and excel in their functional aspects (Ortiz Nicolás

& Schoormans, 2019). Autonomy is achieved when

intrinsic goals are met with the assistance of a product. Four autonomy

constructs have been identified: direction, control, product integration, and

pleasurable effect (Ortiz Nicolás & Schoormans,

2019).

Previous

research on autonomy in person-product interaction has primarily focused on

young adults (Hassenzahl et al., 2010; Ortiz Nicolás

& Schoormans, 2019), neglecting older individuals

with unique characteristics and interests. It is crucial to address this gap in

the field of user experience considering the relevance that autonomy holds for older

populations as previous research has indicated.

This

research aims to understand the autonomy experience of older people with

durable products answering the research question: How

do durable products contribute to the experience of autonomy in older people? The findings have the potential to

enhance autonomous aging, which is defined as the freedom to determine our

actions (Van der Cammen et al., 2017), thus upholding

the rights of older people. Therefore, it is important to investigate how the

experience of autonomy in older people's interaction with products is structured

to establish a practical

framework for incorporating it into the design field.

Methodology

A qualitative study was designed because it aligns with the goal and research question: to understand the autonomy experience of older people with durable products.

Participants

Working with older individuals represent challenges as previous research has reported: “Studying emotions in the older population reports that it is a challenging task” (Kremer & den Uijl, 2016, p. 560) due to the large differences in the size and personal characteristics of the studied populations. Therefore, “the heterogeneity of seniors should be considered when measuring their emotions” (Kremer & den Uijl, 2016, p. 561). We defined specific criteria to reach heterogeneity of the fourteen participants involved in the research: They were Mexican women, being over 60 years old, free of cognitive impairment, Spanish speaking and not affiliated with the design discipline. The average age of the group was 73 years (minimum = 65, maximum = 80). None of the participants had jobs and were dedicated to domestic work. Two participants reported that they were retired or pensioned.

Two participants were invited to the study via social media (WhatsApp and Facebook), while the rest were contacted in person through the Center of Older People from the National System for Integral Family Development (DIF), located in the city of Atlacomulco, Mexico. The interviews took place from April to June 2023.

General Approach and

Selection of Instruments

User experience is a meta process (Russel in Hassenzahl, 2010 p. 3), a rich and complex phenomenon (McCarthy & Wright, 2004) that involves a combination of attributes (Gentner et al., 2013). For example, Hassenzahl (2010) explains that there are three levels 1) the “What” level, 2) the “How” level, and 3) the “Why” level. In product design, the “Why” level is related to people's goals, the “How” level to concrete outcomes, and the “What” level to the steps needed to complete activities.

To study the experience of autonomy in depth, we defined six instruments

to gather different aspects of people's experience (the what, the why

and the who). Two instruments were prepared to explore the experience in detail

through an interview and a written report. The other four instruments have been

validated in the field of user experience (Kujala et

al., 2011; Lenz et al., 2013; Sheldon et al., 2001; Ortiz Nicolás &

Hernández López, 2018). The details of the instruments are presented next:

- A paper sheet format was utilized to report on why the product satisfies autonomy (Appendix A). This tool was crucial to the study as it helped to define autonomy (Sheldon et al., 2001) and provide guidance on selecting a product that enhances it. Participants were then asked to write down the reasons for their selection. The tool was provided at least one day in advance and had to be completed in order to proceed with the interview.

- A semi-structured interview was conducted to understand why and how the product is a means to fulfill autonomy (Appendix B).

- A qualitative method of causal identification of emotions in the person-product interaction applying a set of 30 cards with emotional names to identify recurrent emotions and their eliciting conditions triggered by the product (Ortiz Nicolás & Hernández López, 2018)

- The UX curve method “assists users in retrospectively reporting how and why their experience with a product has changed over time…and enables users and researchers to determine the quality of long-term user experience and the influences that improve user experience over time or cause it to deteriorate” (Kujala et al., 2011, p. 1) (Appendix C).

- A questionnaire focused on understanding interaction qualities based on Lenz and colleagues' vocabulary of interaction, which is “a systematically derived set of interaction attributes to describe interaction in a modality- and technology-free way” (Lenz et al., 2013, p. 1) (Appendix D).

- A questionnaire to identify other psychological needs that the selected product fulfills based on the findings of Sheldon and colleagues (2001) (Appendix E).

Through the first four instruments, we collect verbal and written data. The two questionnaires provide insights into similarities based on issues related to interaction properties and psychological needs.

Procedure

Work groups were

held providing general instructions, subsequently, the participants responded

individually to the instruments used. The procedure for implementing the study

with the participants was structured into three phases and conducted in

Spanish:

I.

Participants

pre-selected a product that met their need for autonomy as defined and completed a form in which they wrote down their reasons explaining

why the chosen product enhances autonomy. When needed, they verbally clarified

some issues related to their written answer. During

the face-to-face session, participants signed an informed consent form, and

questions related to the study were clarified.

II.

Participants

filled out the UX Curve Method (Appendix C), the person-product interaction

questionnaire (Appendix D), and the needs questionnaire (Appendix E).

III.

Participants

were interviewed individually, and the audio was recorded. At the end,

participants selected emotions that they felt with the product and explained

the reasons for experiencing them. They received a gift certificate as a

gratification for their participation.

Data

Organization and Analysis

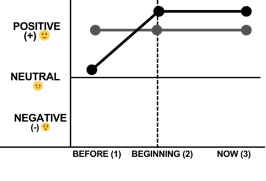

As previously mentioned, we collected verbal and written data, and maps related to the evolution of experience over time (Figure 1). The first step was to organize the verbal data: the interviews, written reports, and explanations related to the emotions experienced as a result of interacting with a product that enhances autonomy and were compiled into a dataset. Interviews were transcribed verbatim using Google's Pinpoint software, and reviewed word by word by the first author applying the constant comparison analysis (Glaser, 1978, 1992; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss, 1987). The data was then coded into categories described in the results, such as reasons that explain why a product enhances autonomy or reasons that evoke a recurrent emotion such as confidence (Ortiz Nicolás & Hernández López, 2018). We achieved theoretical saturation based on the population involved, making the research findings valid.

Figure 1. General trends in the experience map.

The fourteen UX curve maps were

organized to identify general trends. Interaction qualities, and psychological

needs were organized into spreadsheets to identify tendencies, i.e., the most

recurrent interaction properties.

Results

The data gathered, based on a holistic perspective of experience, is reported into three main aspects: the characteristics of the selected products, the role of interaction and activities in the experience of autonomy, and elements that structure the autonomy experience. With this structure we aim to provide a detailed description of the studied experience and answer the research question: How do durable products contribute to the experience of autonomy in older people?

Characteristics of the Selected Products

The

products that satisfied the need for autonomy among the participants were:

iron, reclining armchair, chair, blender, television, microwave oven, washing

machine, electric hairbrush, desk, bed, and laptop (Refer to Table 1 for a

detailed account of the selected products). Half of the participants reported they had recommended the product to

someone else, and four participants said they had more products from the same brand. One person mentioned, “Yes, the refrigerator

and the stove, in addition to the washing machine.”

The

participants reported having the chosen products between 2 to 40 years. Eight out of fourteen bought the product,

while six received it as a gift. Eight out of fourteen said that the product

allowed them to do things their way while also holding personal significance.

For instance, one person explained that her “reclining armchair was meaningful to her because it was given on Father's Day as a gift, recognising her role as a single mother.”

13

out of 14 participants stated that they did not modify the product. The only

person who modified the product attached transparent plastic to a desk to

prevent it from deteriorating. This action, however, did not alter the product's

function. There is a consensus regarding the performance of the selected

products: all of them deliver their instrumental functions very effectively.

The role of interaction and activities in the experience of autonomy

Four product categories that promote autonomy were identified and organized based on specific activities: a) performing domestic tasks; b) relaxing and enjoying free time; c) studying and learning, and d) personal care.

Table 1. Product

categories.

Performing domestic tasks |

Relaxing and enjoying free time |

Studying and learning |

Personal Care |

|

Iron |

Reclining armchair |

Chair (2) |

Electric hairbrush |

|

Blender (2) |

Television (2) |

Desk |

|

|

Microwave oven |

Bed |

Laptop |

|

|

Washing machine |

|

|

|

The relevance of the activities. The products facilitate

important activities for individuals, with 12 out of 14 agreeing. These

activities include cooking, washing and ironing clothes, combing hair,

communicating, entertaining, and staying informed. These activities are

relevant because they are part of daily life routines, such as ironing clothes

and cooking in the microwave. One participant stated that she chose a chair

because she used to study while sitting on it. The activity is “very important to me because I was orphaned at

the age of four, so I stopped studying. Only recently, I did finish high

school.”

The directions of actions performed while

using the product. Half of the people felt responsible for

what happened while using the product. Seven people mentioned that they did not

pay much attention to the product as it often depended on the activity being

done with the product. One participant said: “Well, it depends on what I am watching [on television]

because if it is interesting, I do not distract myself with other things. Other

times, I just listen to TV, while focusing on other important activities, like

painting, drawing, or doing my homework.”

There is no need to develop specific

skills. Twelve

people stated they did not develop any specific skills to use the product,

while one person took computer courses, and another had to read the entire

washing machine manual.

There is little physical or mental effort.

All the individuals reported that using the chosen product required

little physical or mental effort. They declared that when using the product,

they felt supported and sometimes noticed a decrease in physical and mental

strain while carrying out activities with the product. For example, one person

mentioned: “It

[the washing machine] helps me a lot, saving me physical energy and completing

tasks the way I prefer.”

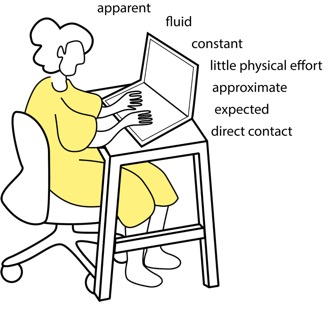

Interaction properties. The most frequent interaction

properties were as follows: apparent (12 out of 14), fluid (10 out of 14),

constant (10 out of 14), and requiring little physical effort (10 out of 14).

Nine out of 14 participants mentioned that the interaction is approximate,

meaning it does not require precision to use the product, the interaction is

expected and there is direct contact (physical) with the product. These

properties are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Interaction properties in the experience of autonomy.

Aspects of Human Experience

The UX curve method. The experience that a person has with

products promoting autonomy is positive. Out of 14 participants, 13 stated

during the interview that their

experience with the product was positive. Two general trends were identified

based on the experience map: either having a positive experience from the start

to the moment of the interview (7 out of 14) or transitioning from neutral to

positive (6 out of 14). Only one person reported having a negative experience

at the time of the interview.

Psychological needs that come with

autonomy. The

chosen products also fulfill competence, physical health, pleasure,

self-actualization, and security. Table 2 presents the number of participants

who selected the reported needs.

Table 2. Psychological

needs that come with autonomy

|

Competence |

13 out of 14 |

Physical health |

13 out of 14 |

|

Pleasure |

12 out of 14 |

Self-actualization |

11 out of 14 |

|

Security |

10 out of 14 |

Self-esteem |

8 out of 14 |

|

Relatedness |

7 out of 14 |

Popularity |

7 out of 14 |

Emotions experienced. The emotions frequently

reported regarding products that enhance an experience of autonomy were

confidence (6), satisfaction (6), joy (5), and pride (4). Confidence was linked

to feeling safe while using the product, knowing it would perform well and not

cause harm. One person stated: “Because

I am sure the food will be ready and well prepared [in the microwave].” Participants felt confident in

their ability to use the product without difficulty, were free to choose, and

felt empowered when completing tasks with the product. Using the product also

gave satisfaction, as another person mentioned: “Satisfaction that I am fine [when using their furniture].”

Some individuals

experienced joy and tranquility, associating these emotions with comfort: “They give me comfort, [referring to their

furniture like the bed and armchair] I can rest, sleep peacefully, renew my

energy, and feel happy and comfortable.”

The experience of autonomy promotes

well-being. Eight

participants reported that their sense of well-being was linked to autonomy.

They understood well-being subjectively, as no specific definition was provided

to them.

Regarding

the blender, one participant stated, “I no longer have to be there with the

sauce [smashing it] ... right now I don't have the strength to be there with

the molcajete.” Another participant mentioned the washing machine saying: “I

can do other things focusing on what I like.”

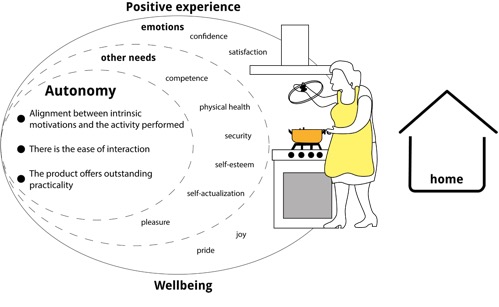

Identifying the Constructs of Autonomy in Older People's Product Interaction

Based on the previously reported

findings, we synthesized the results into four

constructs of autonomy in the interaction between older people and products:

I.

There is an

alignment between intrinsic motivations and the activities performed with the

product. Autonomy is

fulfilled through the product, as it serves as a means to carry out relevant activities for the individuals. Participants

also selected products that hold personal meaning for them. Additionally, other psychological needs such as

competence, physical health, pleasure, self-actualization, security, and

self-esteem are met.

II.

The product

offers outstanding practicality, showcasing a perfect alignment between

people's autonomy and its excellent performance. Participants reported that they did not feel the need to modify the product.

III.

There is

ease of interaction: the interaction is familiar and smooth, with individuals consistently achieving the desired result

without requiring precision or exerting much physical

effort. By providing comfort and independence, the product is considered

reliable. The ease of interaction also indicates that individuals can control and direct the

product.

IV.

The

experience of autonomy is described as pleasant, as evidenced by interview

responses, expressions of positive emotions, self-reports using the UX curve

method, and its positive impact on well-being.

The elements of the

autonomy experience of older people with durable products are illustrated in

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Elements in the autonomy experience of older people with durable products

Discussion

The experience of autonomy in older people is multidimensional and promotes well-being. It is influenced by the fulfillment of other needs such as competence, physical health, security, self-esteem, self-actualization and pleasure. The emotional dimension of autonomy includes confidence, satisfaction, joy, and pride. Besides that, the results indicated that people were familiar with their objects, and they may have learned how to use the product in the past but currently, they focus on the relevant activities rather than the product itself. This implies a ready-to-hand relationship (Heidegger, 2010).

Our findings

reinforce that autonomy is

achieved when a person's intrinsic objectives are met with the support of a

product (Ortiz Nicolás & Schoormans, 2019). Two

activities identified as relevant (education and personal care) align with

Ortiz Nicolás & Schoormans (2019) findings. Furthermore, the focus on significant activities for older people in daily

life is consistent with the findings of Miso and colleagues (2022), Moilanen (2021), and Sánchez-García and colleagues (2019),

who stated that engaging in relevant activities is a key theme related to older

people's autonomy.

Consistent with Zhou and colleagues (2022), interactions should be efficient, minimizing unnecessary steps and making the design convenient and straightforward. These characteristics can impact on a fluent interaction (Pacheco, 2019). We identified differences based on the populations implicated in the present study and past one (Ortiz Nicolás & Schoormans, 2019): younger people tend to select mobile products (Ortiz Nicolás & Schoormans, 2019, p. 4013), while older people prefer products that usually stay in one place. Younger individuals believe that a product enhancing autonomy can be customized to their preferences (Ortiz Nicolás & Schoormans, 2019), while older people do not view this as a significant aspect of autonomy. Referring to interaction attributes, both young and old chose constant and expected (Ortiz Nicolás & Schoormans, 2019, p. 4014).

One implication of the

findings of this study is

the recognition of two constructs of fluent

interaction that can be applied to both young and older people: expected and

constant. It is also relevant to consider how an individual's prior knowledge can be

integrated into a potential solution to enhance the fluidity of interaction in

design practice.

Our findings highlight the importance of identifying the psychological needs of older people to understand their experience with products. Participants reported other psychological needs such as competence, physical health, pleasure, self-actualization, and security, which are all part of the experience of autonomy. Previous research has linked good health, both physical and mental, to autonomy (Sánchez-García et al., 2019) as well as pleasure. This helps explain the relationship between autonomy and physical health. Interestingly, no products related to exercise were reported. It may be associated with the ability of the person to maintain their decisions, complete tasks, and achieve their goals. Therefore, further research is needed to understand the relationship between autonomy and physical health.

In terms of pleasure, designers often overlook its significance in product design for older people, focusing instead on aspects that promote ageism and ableism, which involve the belief that physical health is the only important factor in aging. Reynolds states, “When one becomes comparatively less able due to aging, one's world transforms... ableism is at the core of ageism” (2018, p. 33). As a result, products designed for older people tend to focus on assistive devices like stand-alone toilet safety handrails, mobility scooters, bed assist rails, and adult feeding bibs.

It is crucial to

challenge ageism and ableism when creating health or assistive products for

older people, so designers should acknowledge the role of pleasure as a key

factor in the design process. The overall results emphasize the importance of

understanding how psychological needs are significant to the older population.

Future studies could further explore

the needs associated with the experience of autonomy to investigate various

aspects of each. For example, researchers could analyze how physical health

could be leveraged in the creation of products or services specifically for

older individuals, or how to design enjoyable products for this demographic. An

important topic that should be examined in the future is the consideration of

autonomy as a fundamental human right (Inter-American Convention on the

Protection of the Human Rights of Older Persons, 2017). Understanding how the

concept of autonomy can be integrated into the framework of human rights is

crucial, especially given the limited training that designers in Mexico receive

on human rights and autonomy specifically.

The

right to autonomy can impact design education from various perspectives.

Autonomy is not just an option when designing for older people; it is a legal

aspect that designers need to consider (Inter-American

Convention on the Protection of the Human Rights of Older Persons, 2017). Design schools should evaluate whether

it is significant to incorporate a human rights perspective as a design

strategy, not only for older people, but in general. Other questions related to

design and human rights include: Can designing for autonomy help achieve equality and prevent

discrimination, both of which are fundamental human rights? How does designing

for experience differ from designing for human rights? Does the

psychological need of autonomy help maintain the physical condition of autonomy?

The limitations of this research are

associated with the population itself. Future research should explore other

older population types and variations, such as centenarian people. Practical

implications of our work include applying the information obtained to design

projects to promote the autonomy of the older population.

Conclusion

Autonomy is a relevant issue for humans, especially older people. Therefore, studying it is relevant in the field of user experience to gain knowledge to understand how to design services, experiences and products aimed at this demographic, which is currently an area of opportunity. This research serves as an invitation to further explore this topic and begin incorporating its findings into design practices.

The present study applied six validated instruments from the field of user experience to gain a thorough understanding of autonomy in older individuals during product interactions. The results elucidate the various dimensions of autonomy experience, which includes a product that provides exceptional practicality in line with individuals' goals. Participants consistently achieved their desired outcomes without requiring precision or exerting significant physical effort. The ease of interaction also suggests that individuals can control and guide the product. The products chosen by participants were identified as vital tools that enhance autonomy and well-being.

Autonomy is a human right and should be taken into account in the design of products, services and experiences for older adults. Designers must challenge stereotypes, prejudices and biases about aging and recognize the importance of pleasure, competence and self-actualization in user experience. By doing so, the design process aimed at old adults should evolve. This research not only contributes to existing literature but also provides a practical framework for understanding autonomy in older adults which can guide design processes tailored to this population.

Translation

The translation

takes into account local aspects.

Funding

The DGAPA UNAM Postdoctoral Scholarship Program has funded this work

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the study participants.

References

Bernardini, D. (2023). La segunda mitad. Los 50+ vivir la nueva longevidad. Penguin Random House.

Buedo-Guirado, C., & Rubio Rubio, L. (2018). La innovación del proyecto gerontológico desde la educación social: Efectos sobre bienestar psicológico y subjetivo de personas españolas institucionalizadas. Anales en Gerontología, 10(10), 36–55. https://revistas.ucr.ac.cr/index.php/gerontologia/article/view/28023

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1987). The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(6), 1024–1037. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.6.1024

Desmet, P., & Fokkinga, S. (2020). Beyond Maslow’s pyramid: Introducing a typology of thirteen fundamental needs for human-centered design. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 4(3), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti4030038

Diener, E., & Chan, M. Y. (2011). Happy people live longer: Subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 3(1), 1–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2010.01045.x

Gentner, A., Bouchard, C., & Favart, C. (2013). Investigating user experience as a composition of components and influencing factors. In Proceedings of the International Association of Societies of Design Research Conference (Vol. 142).

Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity. Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (1992). Discovery of grounded theory. Aldine.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine.

Hassenzahl, M. (2010). Experience Design: Technology for All the Right Reasons. Springer Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-02191-6

Heidegger, M. (2010). Being and time. Suny Press.

Inter-American Convention on the Protection of the Human Rights of Older Persons. (2017). Convención Interamericana sobre la Protección de los Derechos Humanos de las Personas Mayores (ONU Registry No. 54318, February 27, 2017).

Kremer, S., & den Uijl, L. (2016). Studying emotions in the elderly. In H. L. Meiselman (Ed.), Emotion Measurement (pp. 537–571). Woodhead Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-100508-8.00022-9

Kujala, S., Roto, V., Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila, K., Karapanos, E., & Sinnelä, A. (2011). UX Curve: A method for evaluating long-term user experience. Interacting with Computers, 23(5), 473–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intcom.2011.06.005

Lawton, M. P., & Brody, E. M. (1969). Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist, 9(3), 179–186.

Liu, L., Daum, C., Cruz, A. M., Neubauer, N., & Ríos Rincón, A. (2022). Ageing, technology, and health: Advancing the concepts of autonomy and independence. Healthcare Management Forum, 35(5), 296–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/08404704221110734

Lenz, E., Diefenbach, S., & Hassenzahl, M. (2013). Exploring relationships between interaction attributes and experience. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Designing Pleasurable Products and Interfaces (pp. 126–135). ACM. http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2513506.2513520

López García, M. M., Aguilar Pérez, L. S., & Mancilla Gallardo, M. de J. (2022). La calidad de vida percibida por personas adultas mayores urbanas no institucionalizadas en Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas. Anales en Gerontología, 14(14), 73–95. https://revistas.ucr.ac.cr/index.php/gerontologia/article/view/50120

Miso, K., Random, V., Pozzar, R., Fombelle, P., Zhou, X., Zhang, Y., & Jiang, M. (2022). Healthy aging adviser: Designing a service to support the life transitions and autonomy of older adults. The Design Journal, 25(2), 143–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2021.2021662

Moilanen, T., Kangasniemi, M., Papinaho, O., Mynttinen, M., Siipi, H., Suominen, S., & Suhonen, R. (2021). Older people’s perceived autonomy in residential care: An integrative review. Nursing Ethics, 28(3), 414–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733020948115

Ortiz Nicolás, J. C., & Hernández López, I. (2018). Emociones específicas en la interacción persona-producto: Un método de identificación causal. Economía Creativa, 9, 122–162. https://doi.org/10.46840/ec.2018.09.06

Ortiz Nicolás, J. C., & Schoormans, J. (2019). The experience of autonomy with durable products. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED19) (pp. 5–8). Delft, Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1017/dsi.2019.408

Ortiz Nicolás, J. C., & Schoormans, J. (2022). La experiencia de autonomía en la interacción persona-producto y su relación con el bienestar. In D. Bedolla Pereda (Ed.), Diseño y afectividad para fomentar bienestar integral (pp. 273–299). UAM, Unidad Cuajimalpa, División de Ciencias de la Comunicación y Diseño. https://doi.org/10.24275/9786072824669

Pacheco, C. N. (2019). Interaction aesthetics in and beyond the flow. Diseña, 15, 48–69. https://doi.org/10.7764/disena.15.48-69

Reynolds, J. M. (2018). The extended body: On aging, disability, and well-being. The Hastings Center Report, 48(5), S31–S36. https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.910

Rivero, A. M. (2018). Aging suit: An accessible and low-cost design tool for the gerontodesign. In Handbook of Research on Ergonomics and Product Design (pp. 56–69). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-5234-5.ch004

Rubio Rubio, L., Dumitrache Dumitrache, C. G., Buedo-Guirado, C., & Cabezas Casado, J. L. (2018). Autoeficacia general percibida y bienestar psicológico. Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología, 53, 61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regg.2018.04.446

Sánchez-García, S., García-Peña, C., Ramírez-García, E., Moreno-Tamayo, K., & Cantú-Quintanilla, G. R. (2019). Decreased autonomy in community-dwelling older adults. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 14, 2041–2053. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S225479

Sheldon, K. M., Elliot, A. J., Kim, Y., & Kasser, T. (2001). What is satisfying about satisfying events? Testing 10 candidate psychological needs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(2), 325–339. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.80.2.325

Strauss, A. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge University Press.

Tierney, L., & Beattie, E. (2020). Enjoyable, engaging and individualised: A concept analysis of meaningful activity for older adults with dementia. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 15(2), e12306. https://doi.org/10.1111/opn.12306

Van der Cammen, T. J. M., Albayrak, A., Voûte, E., & Molenbroek, J. F. M. (2017). New horizons in design for autonomous ageing. Age and Ageing, 46(1), 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw181

World Health Organization. (2019). GHE: Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-life-expectancy-and-healthy-life-expectancy

Zhou, C., Dai, Y., Huang, T., Zhao, H., & Kaner, J. (2022). An empirical study on the influence of smart home interface design on the interaction performance of the elderly. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9105. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159105

Annika

Maya-Rivero

Centro de Investigaciones de Diseño

Industrial de la Facultad de Arquitectura de le Universidad Nacional Autónoma

de México. Académica RIES.LAC.

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2648-4977

Annika

is an Industrial Designer from Universidad Iberoamericana Ciudad de México,

IBERO CDMX. She

holds a Design PhD and a master's in design from the Autonomous University of

the State of Mexico. She was a postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Architecture

Faculty of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Her research areas are

design for aging, design for longevity, and inclusive design.

Juan Carlos

Ortiz-Nicolás

Centro de Investigaciones de Diseño

Industrial de la Facultad de Arquitectura de le Universidad Nacional Autónoma

de México. Académica RIES.LAC.

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2180-1360

Juan

Carlos is an industrial designer who graduated from Centro de Investigaciones

de Diseño Industrial at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, CIDI-UNAM. He completed master's

studies in interaction design and doctoral studies in the field of user

experience. He is a professor of the Postgraduate in Architecture,

Postgraduate, and Bachelor of Industrial Design. His publications cover the

topics of user experience, social innovation, and design education.